Big interview: Alex Glassbrook

Alex Glassbrook, a barrister at Temple Garden Chambers, has written extensively about the law and self-driving cars. He argues that the Department for Transport’s approval of Ford’s hands-free tech is a radical development, that must be accompanied by effective guidance and training for the public and affected organisations.

MotorPro: Why was the Ford hands-free driving announcement so significant?

The first question many of us asked was is this the first automated vehicle under the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018? It appears that it's not. First, because it hasn't been listed under Section 1 of the Act by the Secretary of State. Second, because it seems not to fulfil the criterion of a system that does not need to be monitored by the driver.

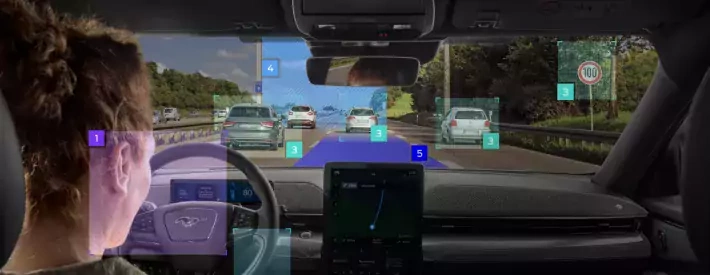

So, what we're looking at is a vehicle with advanced driver assistance, but not a driverless vehicle. Equally, what we're looking at is something that does represent a culture change, because the driver is allowed to remove their hands from the steering wheel.

It's described as a ‘hands off, eyes on’ system, although this hasn't prevented the media reporting it as a driverless system, which has implications for safety. What’s new is the relinquishing of physical control of steering by the human driver – a profound step in both regulatory and practical terms.

What needs to be considered now that hands-free driving is a legal reality in the UK?

Let’s begin with some historical context. Driver assistance systems have been accumulating for some time, but the legal standard for driving has not really altered since 1971. It was then that Lord Denning, in the case of Nettleship v Weston, set what can be summarised as the standard of the reasonably prudent human driver.

It's a largely objective test, and there are some exceptions, but since established it has never been substantially altered. That’s quite surprising because cruise control is now in such common use that you might have expected the standard of care to have been particularised. Now we have a system that explicitly allows the driver to let go of the steering wheel while the car is in motion at motorway speeds. In the coming years, a court might face the question of what standard of attention is required of a driver using a ‘hands off’ system.

The first edition of The Highway Code was published in 1931, sometime after the introduction of the motor car – written guidance which many of us will have looked at. But it isn't meant to be specialist guidance to industry; it's meant to be comprehensible guidance to the public. Advanced driver assistance systems have been regulated ‘quietly’, mainly settled by negotiation at international level and then applied as industrial standards by national approval authorities. ‘Hands free’ driving seems too significant a step for that trend to continue without better education.

How do you suggest the guidance should be changed?

At the moment, the guidance on driver assistance systems, rule 150, says in essence that those systems are only assistive, that you have to be careful and not let your attention be distracted. Is that guidance too general, for a ‘hands off, eyes on’ system which allows the driver to take their hands off the wheel while driving on a motorway? Then there’s rule 160 – “…both hands on the wheel…” – which will presumably need revision.

We need to think practically about the information which people need to use these systems safely, and how best to communicate it. There’s also an argument that we focus too much upon the user. Others affected include those who enforce driving laws and who respond to road traffic collisions, particularly the police and National Highways officers. Then there’s many others who form part of the wider motoring ecosystem. All of these people need to be aware.